[toc]

Production servers can be described as “grown works of functionality”: An unknown number of commands have been applied by various people over time, often in an ad-hoc manner, and written documentation is commonly outdated, if at all present.

Due to the inability to fully understand and entirely reproduce such environments, companies periodically create full server backups to be prepared against server loss. Still, restoring an environment from backups may consume considerable resources with uncertain success and can by no means be compared with the flexibility and agility of being able to rapidly and reliably recreate _any _environment on demand – from development to production:

A deployment pipeline is, in essence implementation of the application’s build, deploy, test and release process.

The pipeline concept itself is in analogy to Lean Manufacturing, where a production line is stopped whenever a defect is detected along its way. The problem is then addressed with immediate attention and corrective measures are taken to minimize the possibility of making the same mistake ever again (Continuous Improvement) – a principle that is crucial in Agile Software Development.

Here is what a deployment pipeline could look like for an application. In general, the process is initiated whenever a developer commits code to a software repository inside the version control system (VCS) such as Subversion or Git. Only when a build passes all stages it is regarded to be of sufficient quality to be released into production (Live Server).

In the commit stage, the developer commits to a repository branch, compiles the code and executes any quick running, environment agnostic tests (mostly unit tests).

The functionality of the new feature is tested against existing functionality on the master branch and if there are no errors and conflicts the merge is successful.

In this stage, the business (requestor), and QA perform manual user acceptance tests as a final verification step.

After having passed all of the previous stages, a successful build is made available as repository branch (master), from where it can be released into production whenever the business is ready.

In Continuous Delivery, as opposed to Continuous Deployment, releasing a build into production is still a semi-automatic process that should require you to do exactly two things: select a build from a list and press the release-button.

Development teams are driven by demand. Infrastructure as code enables you to treat the development of your automated deployment process as an engineering discipline, driven by software development

During an iteration, each team implements and tests its tasks before their correct behavior is demonstrated and verified in front of a greater audience (preferably in front of the requestor).

In a retrospective meeting, the teams discuss what went well, what went not so well and in which ways the workflow could be improved. By enforcing an automated deployment process and treating infrastructure as code you make sure that you end up with deployable code and working environments at the end of each iteration.

From a business perspective, deployment automation allows you to get changes, whether planned or unplanned, into production reliably and quickly. This allows you to gather precious user feedback (which could be as simple as monitoring your users clicking on that “use this new feature” button) as early as possible and develop and maintain software that is lean and that offers features that your users like to use, thereby avoiding software bloat.

- Ubuntu Server 14.04. LTS

- Architecture 64bit

Operating System

- Debian 7.8

- Architecture 64bit

Environment Specification

This configuration is oriented for large environments

Recommended configuration:

- 200 GB of disk volume

- 8 CPU cores

- 16 GB RAM memory

- Cache size based on the amount of recalls and downloads performed

This configuration is oriented for medium environments

Recommended configuration:

- 200 GB of disk volume (raid)

- 4 CPU cores

- 16 GB RAM memory

- Cache size based on the amount of recalls and downloads performed

It focuses around Git as the tool for the versioning of all of our source code.

For a thorough discussion on the pros and cons of Git compared to centralized source code control systems, see the web. There are plenty of flame wars going on there. As a developer, I prefer Git above all other tools around today. Git really changed the way developers think of merging and branching. From the classic CVS/Subversion world I came from, merging/branching has always been considered a bit scary (“beware of merge conflicts, they bite you!”) and something you only do every once in a while.

But with Git, these actions are extremely cheap and simple, and they are considered one of the core parts of your daily workflow, really. For example, in CVS/Subversion books, branching and merging is first discussed in the later chapters (for advanced users), while in everyGitbook, it’s already covered in chapter 3 (basics).

As a consequence of its simplicity and repetitive nature, branching and merging are no longer something to be afraid of. Version control tools are supposed to assist in branching/merging more than anything else.

Enough about the tools, let’s head onto the development model. The model that I’m going to present here is essentially no more than a set of procedures that every team member has to follow in order to come to a managed software development process.

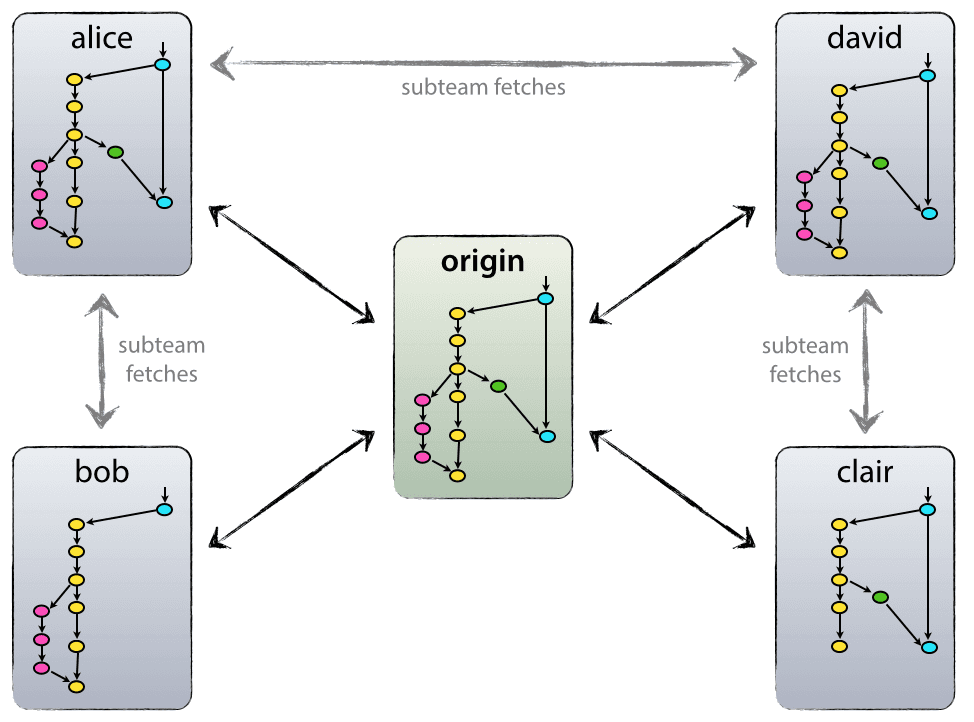

The repository setup that we use and that works well with this branching model, is that with a central “truth” repo. Note that this repo is only considered to be the central one (since Git is a DVCS, there is no such thing as a central repo at a technical level). We will refer to this repo as origin, since this name is familiar to all Git users.

Each developer pulls and pushes to origin. But besides the centralized push-pull relationships, each developer may also pull changes from other peers to form sub teams. For example, this might be useful to work together with two or more developers on a big new feature, before pushing the work in progress to origin prematurely. In the figure above, there are subteams of Alice and Bob, Alice and David, and Clair and David.

Technically, this means nothing more than that Alice has defined a Git remote, named bob, pointing to Bob’s repository, and vice versa.

At the core, the development model is greatly inspired by existing models out there. The central repo holds two main branches with an infinite lifetime:

masterdevelop

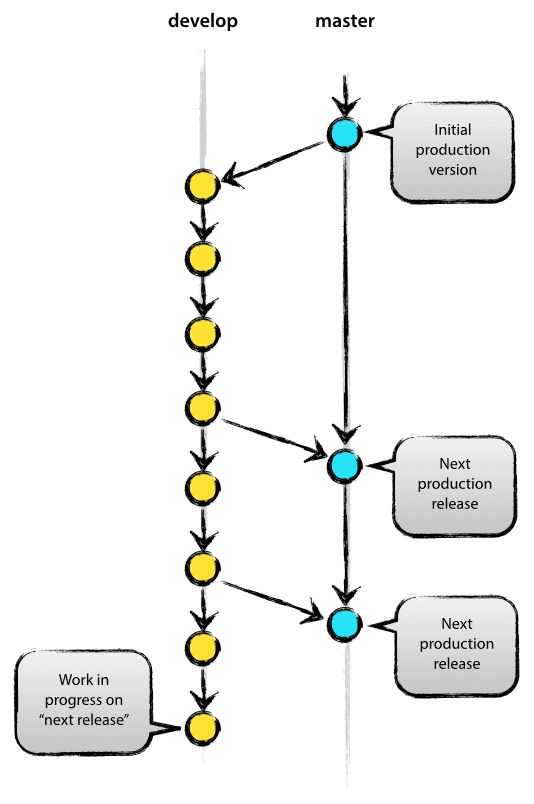

The master branch at origin should be familiar to every Git user. Parallel to the master branch, another branch exists called develop.

We consider origin/master to be the main branch where the source code of HEAD always reflects a production-ready state.

We consider origin/develop to be the main branch where the source code of HEAD always reflects a state with the latest delivered development changes for the next release. Some would call this the “integration branch”. This is where any automatic nightly builds are built from.

When the source code in the develop branch reaches a stable point and is ready to be released, all of the changes should be merged back into master somehow and then tagged with a release number. How this is done in detail will be discussed further on.

Therefore, each time when changes are merged back into master, this is a new production release by definition. We tend to be very strict at this, so that theoretically, we could use a Git hook script to automatically build and roll-out our software to our production servers everytime there was a commit on

master.

Next to the main branches master and develop, our development model uses a variety of supporting branches to aid parallel development between team members, ease tracking of features, prepare for production releases and to assist in quickly fixing live production problems. Unlike the main branches,

these branches always have a limited life time, since they will be removed eventually.

The different types of branches we may use are:

- Feature branches

- Release branches

- Hotfix branches

Each of these branches have a specific purpose and are bound to strict rules as to which branches may be their originating branch and which branches must be their merge targets. We will walk through them in a minute.

By no means are these branches “special” from a technical perspective. The branch types are categorized by how we use them. They are of course plain old Git branches.

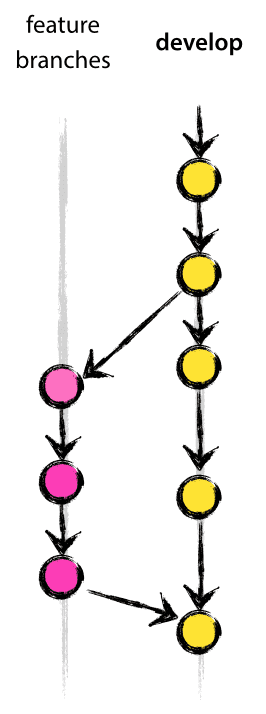

- May branch off from:

developMust merge back into:develop - Branch naming convention: anything except

master,develop,release-*, orhotfix-*

Feature branches (or sometimes called topic branches) are used to develop new features for the upcoming or a distant future release. When starting development of a feature, the target release in which this feature will be

incorporated may well be unknown a that point. The essence of a feature branch is that it exists as long as the feature is in development, but will eventually be merged back into develop (to definitely add the new feature to the upcoming release) or discarded (in case of a disappointing experiment).

Feature branches typically exist in developer repos only, not in origin.

When starting work on a new feature, branch off from the develop branch.

Finished features may be merged into the develop branch definitely add them

to the upcoming release:

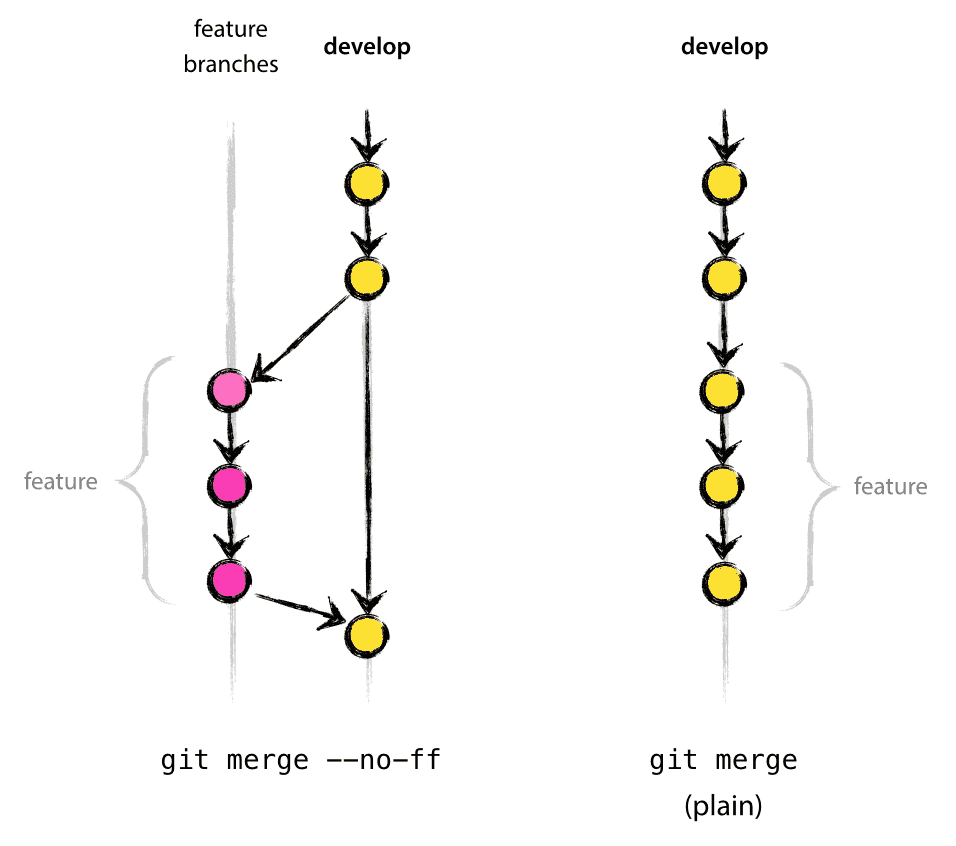

The --no-ff flag causes the merge to always create a new commit object, even if the merge could be performed with a fast-forward. This avoids losing information about the historical existence of a feature branch and groups together all commits that together added the feature. Compare:

In the latter case, it is impossible to see from the Git history which of the commit objects together have implemented a feature—you would have to manually read all the log messages. Reverting a whole feature (i.e. a group of commits), is a true headache in the latter situation, whereas it is easily done if the --no-ff flag was used.

Yes, it will create a few more (empty) commit objects, but the gain is much bigger that that cost.

Unfortunately, I have not found a way to make --no-ff the default behaviour of git merge yet, but it really should be.

- May branch off from:

developMust merge back into:developandmaster - Branch naming convention:

release-*

Release branches support preparation of a new production release. They allow for last-minute dotting of i’s and crossing t’s. Furthermore, they allow for minor bug fixes and preparing meta-data for a release (version number, build dates, etc.). By doing all of this work on a release branch, the develop branch is cleared to receive features for the next big release.

The key moment to branch off a new release branch from develop is when develop (almost) reflects the desired state of the new release. At least all features that are targeted for the release-to-be-built must be merged in to develop at this point in time. All features targeted at future releases may not—they must wait until after the release branch is branched off.

It is exactly at the start of a release branch that the upcoming release gets assigned a version number—not any earlier. Up until that moment, the develop branch reflected changes for the “next release”, but it is unclear whether that “next release” will eventually become 0.3 or 1.0, until the release branch is started. That decision is made on the start of the release branch and is carried out by the project’s rules on version number bumping.

Release branches are created from the develop branch. For example, say version 1.1.5 is the current production release and we have a big release coming up. The state of develop is ready for the “next release” and we have decided that this will become version 1.2 (rather than 1.1.6 or 2.0). So we branch off and give the release branch a name reflecting the new version number:

After creating a new branch and switching to it, we bump the version number. Here, bump-version.sh is a fictional shell script that changes some files in the working copy to reflect the new version. (This can of course be a manual change—the point being that some files change.) Then, the bumped version number is committed.

This new branch may exist there for a while, until the release may be rolled out definitely. During that time, bug fixes may be applied in this branch (rather than on the develop branch). Adding large new features here is strictly prohibited. They must be merged into develop, and therefore, wait for the next big release.

When the state of the release branch is ready to become a real release, some actions need to be carried out. First, the release branch is merged into master (since every commit on master is a new release by definition, remember). Next, that commit on master must be tagged for easy future reference to this historical version. Finally, the changes made on the release branch need to be merged back into develop, so that future releases also contain these bug fixes.

The first two steps in Git:

The release is now done, and tagged for future reference.

Edit: You might as well want to use the

-sor-u <key>flags to sign your tag cryptographically.

To keep the changes made in the release branch, we need to merge those back into develop, though. In Git:

This step may well lead to a merge conflict (probably even, since we have changed the version number). If so, fix it and commit.

Now we are really done and the release branch may be removed, since we don’t need it anymore:

- May branch off from:

masterMust merge back into:developandmaster - Branch naming convention:

hotfix-*

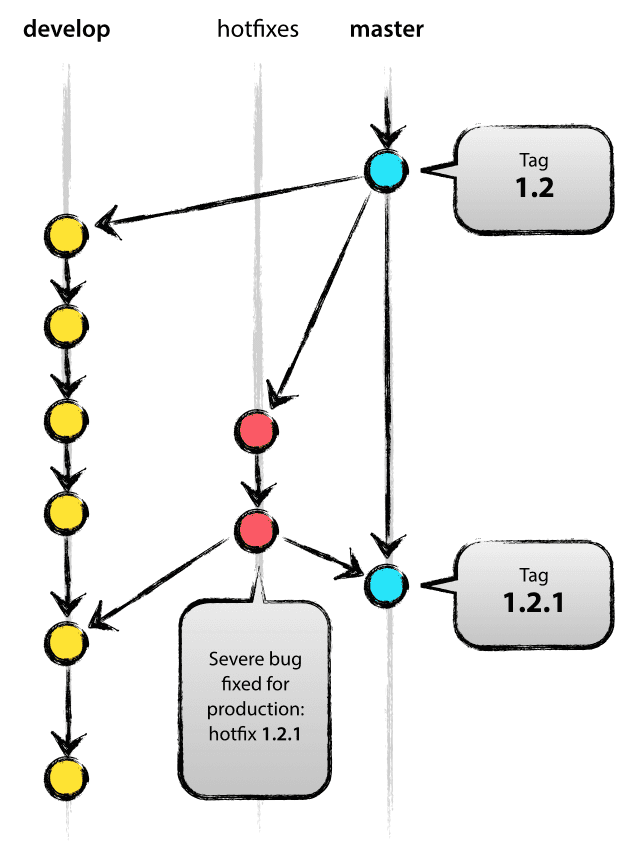

Hotfix branches are very much like release branches in that they are also meant to prepare for a new production release, albeit unplanned. They arise from the necessity to act immediately upon an undesired state of a live production version. When a critical bug in a production version must be resolved immediately, a hotfix branch may be branched off from the corresponding tag on the master branch that marks the production version.

The essence is that work of team members (on the develop branch) can continue, while another person is preparing a quick production fix.

Hotfix branches are created from the master branch. For example, say version 1.2 is the current production release running live and causing troubles due to a severe bug. But changes on develop are yet unstable. We may then branch off a hotfix branch and start fixing the problem:

Don’t forget to bump the version number after branching off!

Then, fix the bug and commit the fix in one or more separate commits.

Finishing a hotfix branch

When finished, the bugfix needs to be merged back into master, but also needs to be merged back into develop, in order to safeguard that the bugfix is included in the next release as well. This is completely similar to how release branches are finished.

First, update master and tag the release.

Edit: You might as well want to use the

-sor-u <key>flags to sign our tag cryptographically.

Next, include the bugfix in develop, too:

The one exception to the rule here is that, when a release branch currently exists, the hotfix changes need to be merged into that release branch, instead of develop. Back-merging the bugfix into the release branch will eventually result in the bugfix being merged into develop too, when the release branch is finished. (If work in develop immediately requires this bugfix and cannot wait for the release branch to be finished, you may safely merge the bugfix into develop now already as well.)

Finally, remove the temporary branch:

While there is nothing really shocking new to this branching model, the “big picture” figure that this post began with has turned out to be tremendously useful in our projects. It forms an elegant mental model that is easy to comprehend and allows team members to develop a shared understanding of the branching and releasing processes.