Stheno is an implementation of Gaussian process modelling in Python. See also Stheno.jl.

- Nonlinear Regression in 20 Seconds

- Installation

- Manual

- Examples

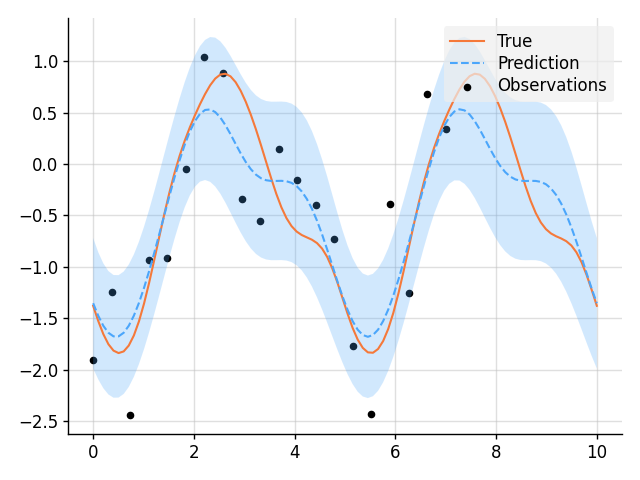

- Simple Regression

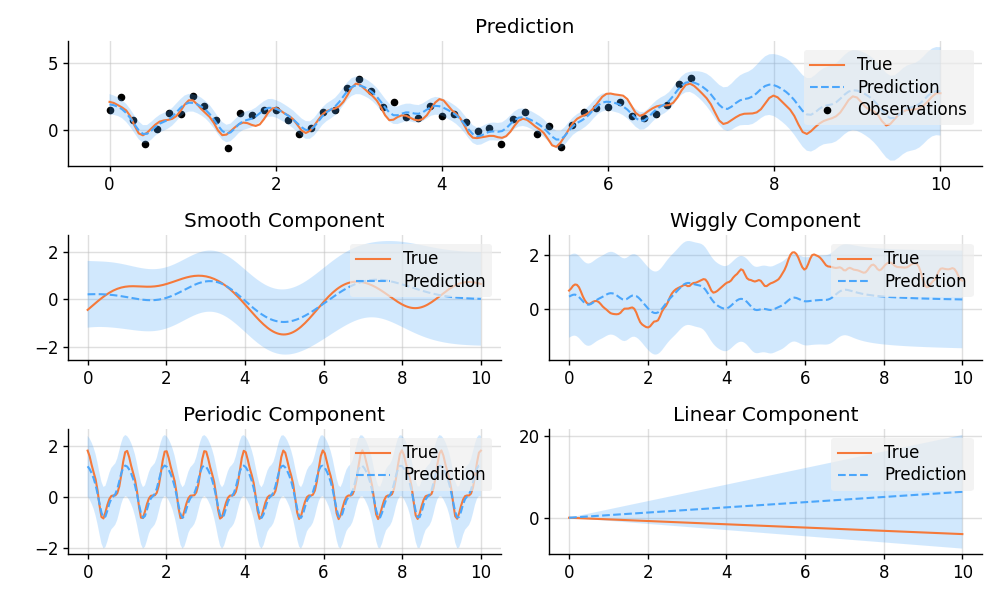

- Decomposition of Prediction

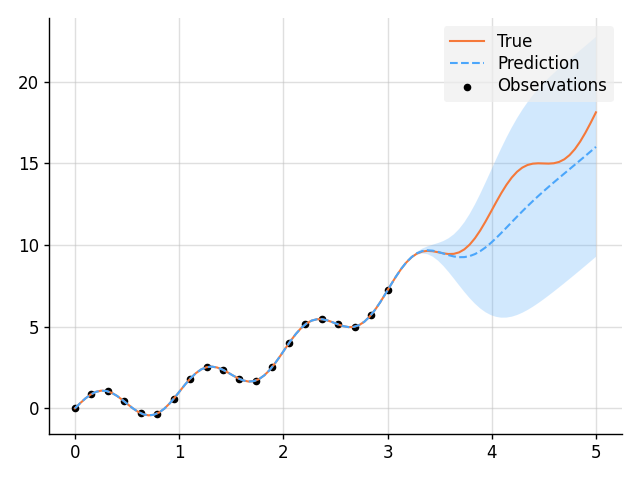

- Learn a Function, Incorporating Prior Knowledge About Its Form

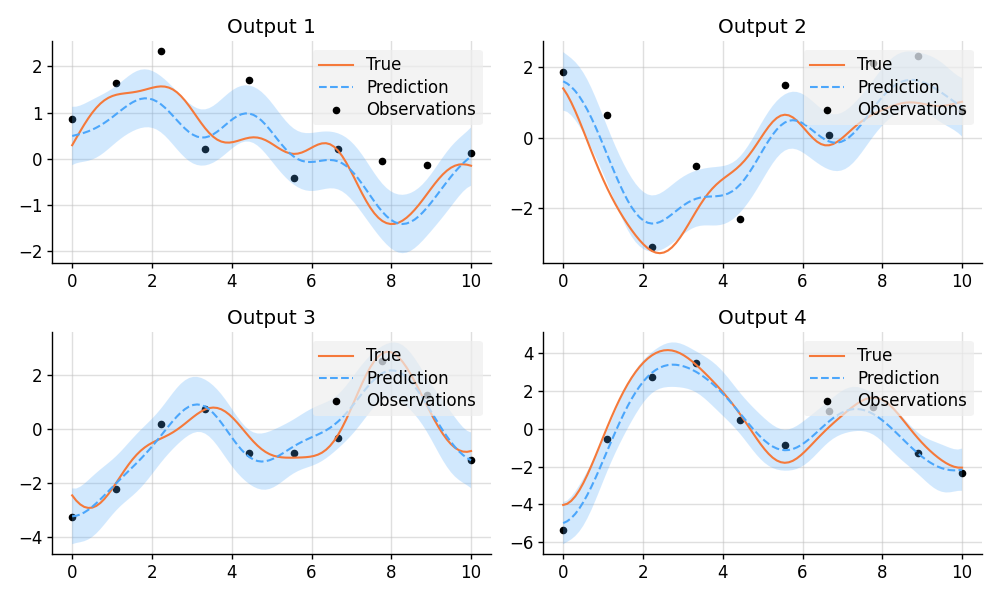

- Multi-Output Regression

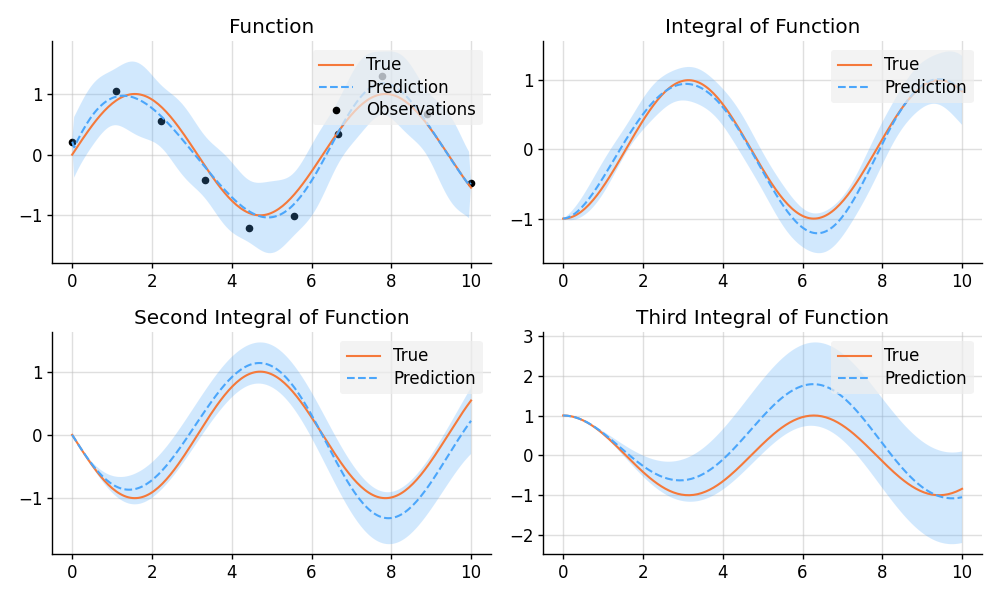

- Approximate Integration

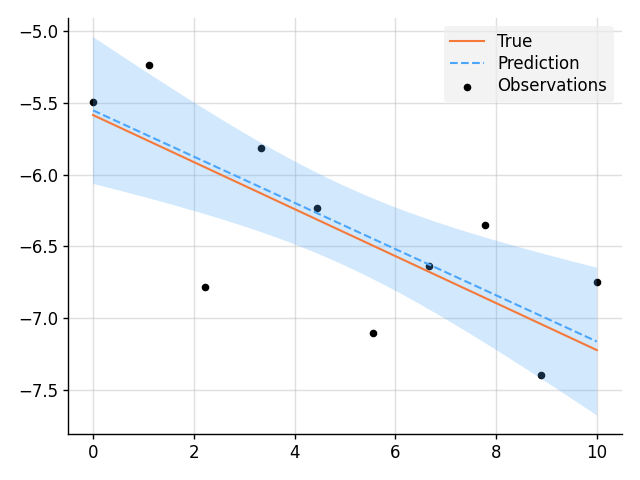

- Bayesian Linear Regression

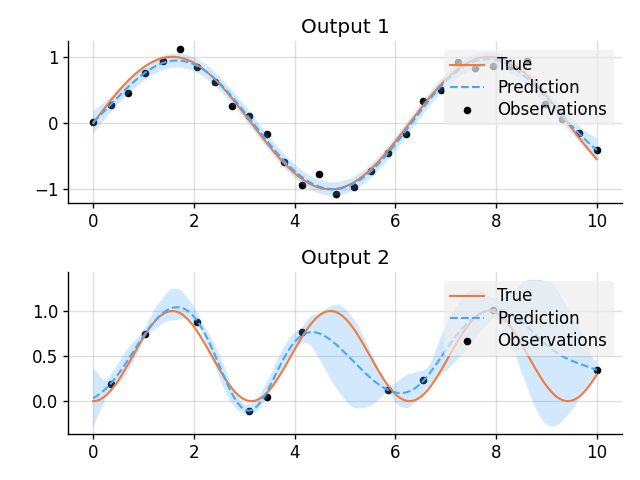

- GPAR

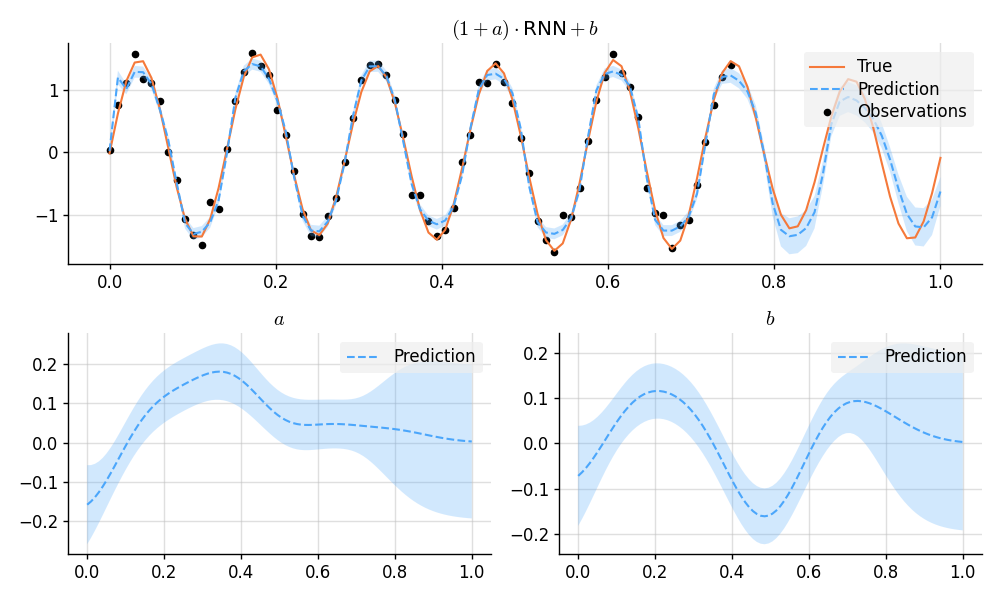

- A GP-RNN Model

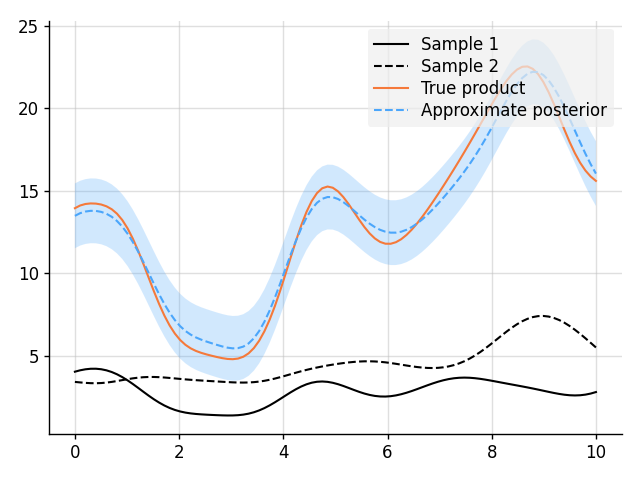

- Approximate Multiplication Between GPs

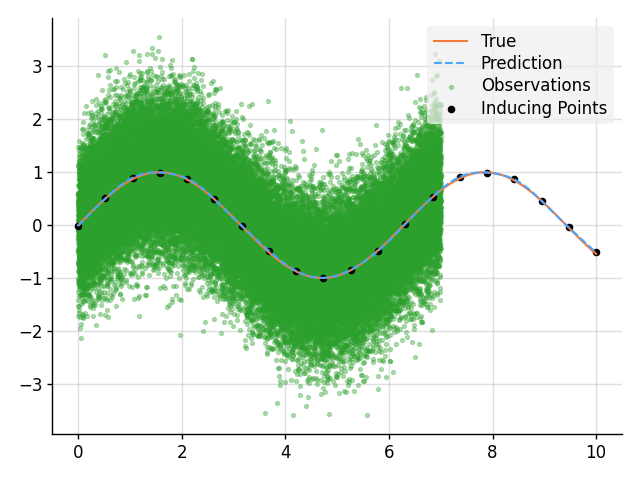

- Sparse Regression

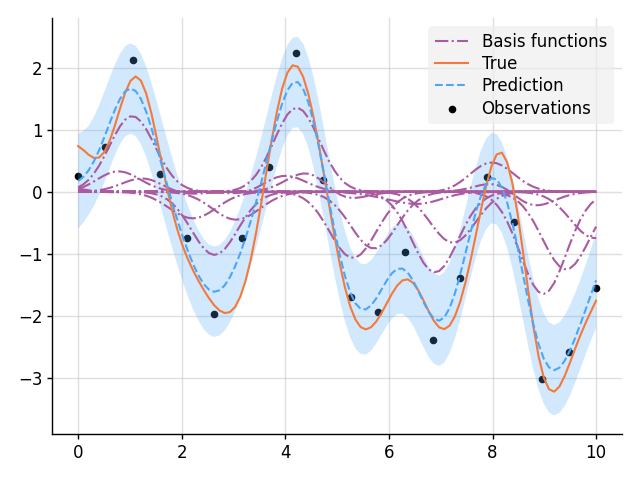

- Smoothing with Nonparametric Basis Functions

>>> import numpy as np

>>> from stheno import Measure, GP, EQ

>>> x = np.linspace(0, 2, 10) # Some points to predict at

>>> y = x ** 2 # Some observations

>>> prior = Measure() # Construct a prior.

>>> f = GP(EQ(), measure=prior) # Define our probabilistic model.

>>> post = prior | (f(x), y) # Compute the posterior distribution.

>>> post(f).mean(np.array([1, 2, 3])) # Predict!

<dense matrix: shape=3x1, dtype=float64

mat=[[1. ]

[4. ]

[8.483]]>Moar?! Then read on!

See the instructions here. Then simply

pip install stheno

Note: here is a nicely rendered and more readable version of the docs.

from stheno.autograd import GP, EQfrom stheno.tensorflow import GP, EQfrom stheno.torch import GP, EQfrom stheno.jax import GP, EQStheno uses LAB to provide an implementation that is backend agnostic. Moreover, Stheno uses an extension of LAB to accelerate linear algebra with structured linear algebra primitives. You will encounter these primitives:

>>> k = 2 * Delta()

>>> x = np.linspace(0, 5, 10)

>>> k(x)

<diagonal matrix: shape=10x10, dtype=float64

diag=[2. 2. 2. 2. 2. 2. 2. 2. 2. 2.]>If you're using LAB to further process these matrices, then there is absolutely no need to worry: these structured matrix types know how to add, multiply, and do other linear algebra operations.

>>> import lab as B

>>> B.matmul(k(x), k(x))

<diagonal matrix: shape=10x10, dtype=float64

diag=[4. 4. 4. 4. 4. 4. 4. 4. 4. 4.]>If you're not using LAB, you can convert these

structured primitives to regular NumPy/TensorFlow/PyTorch/Jax arrays by calling

B.dense (B is from LAB):

>>> import lab as B

>>> B.dense(k(x))

array([[2., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 2., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 2., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., 2., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., 0., 2., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 2., 0., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 2., 0., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 2., 0., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 2., 0.],

[0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 2.]])Furthermore, before computing a Cholesky decomposition, Stheno always adds a minuscule

diagonal to prevent the Cholesky decomposition from failing due to positive

indefiniteness caused by numerical noise.

You can change the magnitude of this diagonal by changing B.epsilon:

>>> import lab as B

>>> B.epsilon = 1e-12 # Default regularisation

>>> B.epsilon = 1e-8 # Strong regularisationThe basic building block is a f = GP(mean=0, kernel, measure=prior), which takes

in a mean, a kernel, and a measure.

The mean and kernel of a GP can be extracted with f.mean and f.kernel.

The measure should be thought of as a big joint distribution that assigns a mean and

a kernel to every variable f.

A measure can be created with prior = Measure().

A GP f can have different means and kernels under different measures.

For example, under some prior measure, f can have an EQ() kernel; but, under some

posterior measure, f has a kernel that is determined by the posterior distribution

of a GP.

We will see later how posterior measures can be constructed.

The measure with which a f = GP(kernel, measure=prior) is constructed can be

extracted with f.measure == prior.

If the keyword argument measure is not set, then automatically a new measure is

created, which afterwards can be extracted with f.measure.

Definition, where prior = Measure():

f = GP(kernel)

f = GP(mean, kernel)

f = GP(kernel, measure=prior)

f = GP(mean, kernel, measure=prior)GPs that are associated to the same measure can be combined into new GPs, which is the primary mechanism used to build cool models.

Here's an example model:

>>> prior = Measure()

>>> f1 = GP(lambda x: x ** 2, EQ(), measure=prior)

>>> f1

GP(<lambda>, EQ())

>>> f2 = GP(Linear(), measure=prior)

>>> f2

GP(0, Linear())

>>> f_sum = f1 + f2

>>> f_sum

GP(<lambda>, EQ() + Linear())

>>> f_sum + GP(EQ()) # Not valid: `GP(EQ())` belongs to a new measure!

AssertionError: Processes GP(<lambda>, EQ() + Linear()) and GP(0, EQ()) are associated to different measures.-

Add and subtract GPs and other objects.

Example:

>>> GP(EQ(), measure=prior) + GP(Exp(), measure=prior) GP(0, EQ() + Exp()) >>> GP(EQ(), measure=prior) + GP(EQ(), measure=prior) GP(0, 2 * EQ()) >>> GP(EQ()) + 1 GP(1, EQ()) >>> GP(EQ()) + 0 GP(0, EQ()) >>> GP(EQ()) + (lambda x: x ** 2) GP(<lambda>, EQ()) >>> GP(2, EQ(), measure=prior) - GP(1, EQ(), measure=prior) GP(1, 2 * EQ())

-

Add and subtract GPs and other objects.

Warning: The product of two GPs it not a Gaussian process. Stheno approximates the resulting process by moment matching.

Example:

>>> GP(1, EQ(), measure=prior) * GP(1, Exp(), measure=prior) GP(<lambda> + <lambda> + -1 * 1, <lambda> * Exp() + <lambda> * EQ() + EQ() * Exp()) >>> 2 * GP(EQ()) GP(2, 2 * EQ()) >>> 0 * GP(EQ()) GP(0, 0) >>> (lambda x: x) * GP(EQ()) GP(0, <lambda> * EQ())

-

Shift GPs.

Example:

>>> GP(EQ()).shift(1) GP(0, EQ() shift 1)

-

Stretch GPs.

Example:

>>> GP(EQ()).stretch(2) GP(0, EQ() > 2)

The

>operator is implemented to provide a shorthand for stretching:>>> GP(EQ()) > 2 GP(0, EQ() > 2)

-

Select particular input dimensions.

Example:

>>> GP(EQ()).select(1, 3) GP(0, EQ() : [1, 3])

Indexing is implemented to provide a a shorthand for selecting input dimensions:

>>> GP(EQ())[1, 3] GP(0, EQ() : [1, 3])

-

Transform the input.

Example:

>>> GP(EQ()).transform(f) GP(0, EQ() transform f)

-

Numerically take the derivative of a GP. The argument specifies which dimension to take the derivative with respect to.

Example:

>>> GP(EQ()).diff(1) GP(0, d(1) EQ())

-

Construct a finite difference estimate of the derivative of a GP. See

stheno.measure.Measure.diff_approxfor a description of the arguments.Example:

>>> GP(EQ()).diff_approx(deriv=1, order=2) GP(50000000.0 * (0.5 * EQ() + 0.5 * ((-0.5 * (EQ() shift (0.0001414213562373095, 0))) shift (0, -0.0001414213562373095)) + 0.5 * ((-0.5 * (EQ() shift (0, 0.0001414213562373095))) shift (-0.0001414213562373095, 0))), 0)

-

Construct the Cartesian product of a collection of GPs.

Example:

>>> prior = Measure() >>> f1, f2 = GP(EQ(), measure=prior), GP(EQ(), measure=prior) >>> cross(f1, f2) GP(MultiOutputMean(0, 0), MultiOutputKernel(EQ(), EQ()))

Like means and kernels, GPs have a display method that accepts a formatter.

Example:

>>> print(GP(2.12345 * EQ()).display(lambda x: '{:.2f}'.format(x)))

GP(2.12 * EQ(), 0)Properties of kernels can be queried on GPs directly.

Example:

>>> GP(EQ()).stationary

TrueIt is possible to give a name to a GP. Names must be strings. A measure then behaves like a two-way dictionary between GPs and their names.

Example:

>>> prior = Measure()

>>> p = GP(EQ(), name='name', measure=prior)

>>> p.name

'name'

>>> p.name = 'alternative_name'

>>> prior['alternative_name']

GP(0, EQ())

>>> prior[p]

'alternative_name'Simply call a GP to construct a finite-dimensional distribution. You can then compute the mean, the variance, sample, or compute a logpdf.

Example:

>>> prior = Measure()

>>> f = GP(EQ(), measure=prior)

>>> x = np.array([0., 1., 2.])

>>> f(x)

FDD(GP(0, EQ()), array([0., 1., 2.]))

>>> f(x).mean

array([[0.],

[0.],

[0.]])

>>> f(x).var

<dense matrix: shape=3x3, dtype=float64

mat=[[1. 0.607 0.135]

[0.607 1. 0.607]

[0.135 0.607 1. ]]>

>>> y1 = f(x).sample()

>>> y1

array([[-0.45172746],

[ 0.46581948],

[ 0.78929767]])

>>> f(x).logpdf(y1)

-2.811609567720761

>>> y2 = f(x).sample(2)

array([[-0.43771276, -2.36741858],

[ 0.86080043, -1.22503079],

[ 2.15779126, -0.75319405]]

>>> f(x).logpdf(y2)

array([-4.82949038, -5.40084225])-

Use

f(x).marginals()to efficiently compute the means and the marginal lower and upper 95% central credible region bounds.Example:

>>> f(x).marginals() (array([0., 0., 0.]), array([-1.96, -1.96, -1.96]), array([1.96, 1.96, 1.96]))

-

Use

Measure.logpdfto compute the joint logpdf of multiple observations.Definition:

prior.logpdf(f(x), y) prior.logpdf((f1(x1), y1), (f2(x2), y2), ...)

-

Use

Measure.sampleto jointly sample multiple observations.Definition, where

prior = Measure():sample = prior.sample(f(x)) sample1, sample2, ... = prior.sample(f1(x1), f2(x2), ...)

Conditioning a prior measure on observations gives a posterior measure.

To condition a measure on observations, use Measure.__or__.

Definition, where prior = Measure() and f* and g* are GPs:

post = prior | (f(x), y)

post = prior | ((f1(x1), y1), (f2(x2), y2), ...)You can then obtain a posterior process with post(f) and a finite-dimensional

distribution under the posterior with post(f(x)).

Let's consider an example. First, build a model and sample some values.

>>> prior = Measure()

>>> f = GP(EQ(), measure=prior)

>>> x = np.array([0., 1., 2.])

>>> y = f(x).sample()Then compute the posterior measure.

>>> post = prior | (f(x), y)

>>> post(f)

GP(PosteriorMean(), PosteriorKernel())

>>> post(f).mean(x)

<dense matrix: shape=3x1, dtype=float64

mat=[[ 0.412]

[-0.811]

[-0.933]]>

>>> post(f).kernel(x)

<dense matrix: shape=3x3, dtype=float64

mat=[[1.e-12 0.e+00 0.e+00]

[0.e+00 1.e-12 0.e+00]

[0.e+00 0.e+00 1.e-12]]>

>>> post(f(x))

<stheno.random.Normal at 0x7fa6d7f8c358>

>>> post(f(x)).mean

<dense matrix: shape=3x1, dtype=float64

mat=[[ 0.412]

[-0.811]

[-0.933]]>

>>> post(f(x)).var

<dense matrix: shape=3x3, dtype=float64

mat=[[1.e-12 0.e+00 0.e+00]

[0.e+00 1.e-12 0.e+00]

[0.e+00 0.e+00 1.e-12]]>We can further extend our model by building on the posterior.

>>> g = GP(Linear(), measure=post)

>>> f_sum = post(f) + g

>>> f_sum

GP(PosteriorMean(), PosteriorKernel() + Linear())However, what we cannot do is mixing the prior and posterior.

>>> f + g

AssertionError: Processes GP(0, EQ()) and GP(0, Linear()) are associated to different measures.Stheno supports sparse approximations of posterior distributions.

To construct a sparse approximation, use Measure.SparseObs.

Definition:

obs = SparseObs(u(z), # FDD of inducing points.

e, # Independent, additive noise process.

f(x), # FDD of observations _without_ the noise process added.

y) # Observations.

obs = SparseObs(u(z), e, f(x), y)

obs = SparseObs(u(z), (e1, f1(x1), y1), (e2, f2(x2), y2), ...)

obs = SparseObs((u1(z1), u2(z2), ...), e, f(x), y)

obs = SparseObs((u1(z1), u2(z2), ...), (e1, f1(x1), y1), (e2, f2(x2), y2), ...)The approximate posterior measure can be constructed with prior | obs

where prior = Measure() is the measure of your model.

To quantify the quality of the approximation, you can compute the ELBO with

obs.elbo(prior).

Let's consider an example. First, build a model that incorporates noise and sample some observations.

>>> prior = Measure()

>>> f = GP(EQ(), measure=prior)

>>> e = GP(Delta(), measure=prior)

>>> y = f + e

>>> x_obs = np.linspace(0, 10, 2000)

>>> y_obs = y(x_obs).sample()Ouch, computing the logpdf is quite slow:

>>> %timeit y(x_obs).logpdf(y_obs)

219 ms ± 35.7 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10 loops each)Let's try to use inducing points to speed this up.

>>> x_ind = np.linspace(0, 10, 100)

>>> u = f(x_ind) # FDD of inducing points.

>>> %timeit SparseObs(u, e, f(x_obs), y_obs).elbo(prior)

9.8 ms ± 181 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100 loops each)Much better. And the approximation is good:

>>> SparseObs(u, e, f(x_obs), y_obs).elbo(prior) - y(x_obs).logpdf(y_obs)

-3.537934389896691e-10We finally construct the approximate posterior measure:

>>> post_approx = prior | SparseObs(u, e, f(x_obs), y_obs)

>>> post_approx(f(x_obs)).mean

<dense matrix: shape=2000x1, dtype=float64

mat=[[0.469]

[0.468]

[0.467]

...

[1.09 ]

[1.09 ]

[1.091]]>Inputs to kernels, means, and GPs, henceforth referred to simply as inputs, must be of one of the following three forms:

-

If the input

xis a rank 0 tensor, i.e. a scalar, thenxrefers to a single input location. For example,0simply refers to the sole input location0. -

If the input

xis a rank 1 tensor, then every element ofxis interpreted as a separate input location. For example,np.linspace(0, 1, 10)generates 10 different input locations ranging from0to1. -

If the input

xis a rank 2 tensor, then every row ofxis interpreted as a separate input location. In this case inputs are multi-dimensional, and the columns correspond to the various input dimensions.

If k is a kernel, say k = EQ(), then k(x, y) constructs the kernel

matrix for all pairs of points between x and y. k(x) is shorthand for

k(x, x). Furthermore, k.elwise(x, y) constructs the kernel vector pairing

the points in x and y element wise, which will be a rank 2 column vector.

Example:

>>> EQ()(np.linspace(0, 1, 3))

array([[1. , 0.8824969 , 0.60653066],

[0.8824969 , 1. , 0.8824969 ],

[0.60653066, 0.8824969 , 1. ]])

>>> EQ().elwise(np.linspace(0, 1, 3), 0)

array([[1. ],

[0.8824969 ],

[0.60653066]])Finally, mean functions always output a rank 2 column vector.

Constants function as constant means. Besides that, the following means are available:

-

TensorProductMean(f):$$ m(x) = f(x). $$ Adding or multiplying a

FunctionTypefto or with a mean will automatically translateftoTensorProductMean(f). For example,f * mwill translate toTensorProductMean(f) * m, andf + mwill translate toTensorProductMean(f) + m.

Constants function as constant kernels. Besides that, the following kernels are available:

-

EQ(), the exponentiated quadratic:$$ k(x, y) = \exp\left( -\frac{1}{2}|x - y|^2 \right); $$

-

RQ(alpha), the rational quadratic:$$ k(x, y) = \left( 1 + \frac{|x - y|^2}{2 \alpha} \right)^{-\alpha}; $$

-

Exp()orMatern12(), the exponential kernel:$$ k(x, y) = \exp\left( -|x - y| \right); $$

-

Matern32(), the Matern–3/2 kernel:$$ k(x, y) = \left( 1 + \sqrt{3}|x - y| \right)\exp\left(-\sqrt{3}|x - y|\right); $$

-

Matern52(), the Matern–5/2 kernel:$$ k(x, y) = \left( 1 + \sqrt{5}|x - y| + \frac{5}{3} |x - y|^2 \right)\exp\left(-\sqrt{3}|x - y|\right); $$

-

Delta(), the Kronecker delta kernel:$$ k(x, y) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } x = y, \ 0 & \text{otherwise}; \end{cases} $$

-

DecayingKernel(alpha, beta):$$ k(x, y) = \frac{|\beta|^\alpha}{|x + y + \beta|^\alpha}; $$

-

LogKernel():$$ k(x, y) = \frac{\log(1 + |x - y|)}{|x - y|}; $$

-

TensorProductKernel(f):$$ k(x, y) = f(x)f(y). $$

Adding or multiplying a

FunctionTypefto or with a kernel will automatically translateftoTensorProductKernel(f). For example,f * kwill translate toTensorProductKernel(f) * k, andf + kwill translate toTensorProductKernel(f) + k.

-

Add and subtract means and kernels.

Example:

>>> EQ() + Exp() EQ() + Exp() >>> EQ() + EQ() 2 * EQ() >>> EQ() + 1 EQ() + 1 >>> EQ() + 0 EQ() >>> EQ() - Exp() EQ() - Exp() >>> EQ() - EQ() 0

-

Multiply means and kernels.

Example:

>>> EQ() * Exp() EQ() * Exp() >>> 2 * EQ() 2 * EQ() >>> 0 * EQ() 0

-

Shift means and kernels:

Definition:

k.shift(c)(x, y) == k(x - c, y - c) k.shift(c1, c2)(x, y) == k(x - c1, y - c2)

Example:

>>> Linear().shift(1) Linear() shift 1 >>> EQ().shift(1, 2) EQ() shift (1, 2)

-

Stretch means and kernels.

Definition:

k.stretch(c)(x, y) == k(x / c, y / c) k.stretch(c1, c2)(x, y) == k(x / c1, y / c2)

Example:

>>> EQ().stretch(2) EQ() > 2 >>> EQ().stretch(2, 3) EQ() > (2, 3)

The

>operator is implemented to provide a shorthand for stretching:>>> EQ() > 2 EQ() > 2

-

Select particular input dimensions of means and kernels.

Definition:

k.select([0])(x, y) == k(x[:, 0], y[:, 0]) k.select([0, 1])(x, y) == k(x[:, [0, 1]], y[:, [0, 1]]) k.select([0], [1])(x, y) == k(x[:, 0], y[:, 1]) k.select(None, [1])(x, y) == k(x, y[:, 1])

Example:

>>> EQ().select([0]) EQ() : [0] >>> EQ().select([0, 1]) EQ() : [0, 1] >>> EQ().select([0], [1]) EQ() : ([0], [1]) >>> EQ().select(None, [1]) EQ() : (None, [1])

-

Transform the inputs of means and kernels.

Definition:

k.transform(f)(x, y) == k(f(x), f(y)) k.transform(f1, f2)(x, y) == k(f1(x), f2(y)) k.transform(None, f)(x, y) == k(x, f(y))

Example:

>>> EQ().transform(f) EQ() transform f >>> EQ().transform(f1, f2) EQ() transform (f1, f2) >>> EQ().transform(None, f) EQ() transform (None, f)

-

Numerically, but efficiently, take derivatives of means and kernels. This currently only works in TensorFlow.

Definition:

k.diff(0)(x, y) == d/d(x[:, 0]) d/d(y[:, 0]) k(x, y) k.diff(0, 1)(x, y) == d/d(x[:, 0]) d/d(y[:, 1]) k(x, y) k.diff(None, 1)(x, y) == d/d(y[:, 1]) k(x, y)

Example:

>>> EQ().diff(0) d(0) EQ() >>> EQ().diff(0, 1) d(0, 1) EQ() >>> EQ().diff(None, 1) d(None, 1) EQ()

-

Make kernels periodic. This is not implemented for means.

Definition:

k.periodic(2 pi / w)(x, y) == k((sin(w * x), cos(w * x)), (sin(w * y), cos(w * y)))

Example:

>>> EQ().periodic(1) EQ() per 1

-

Reverse the arguments of kernels. This does not apply to means.

Definition:

reversed(k)(x, y) == k(y, x)

Example:

>>> reversed(Linear()) Reversed(Linear())

-

Extract terms and factors from sums and products respectively of means and kernels.

Example:

>>> (EQ() + RQ(0.1) + Linear()).term(1) RQ(0.1) >>> (2 * EQ() * Linear).factor(0) 2

Kernels and means "wrapping" others can be "unwrapped" by indexing

k[0]orm[0].Example:

>>> reversed(Linear()) Reversed(Linear()) >>> reversed(Linear())[0] Linear() >>> EQ().periodic(1) EQ() per 1 >>> EQ().periodic(1)[0] EQ()

Kernels and means have a display method.

The display method accepts a callable formatter that will be applied before any value

is printed.

This comes in handy when pretty printing kernels.

Example:

>>> print((2.12345 * EQ()).display(lambda x: f"{x:.2f}"))

2.12 * EQ(), 0-

Means and kernels can be equated to check for equality. This will attempt basic algebraic manipulations. If the means and kernels are not equal or equality cannot be proved,

Falseis returned.Example of equating kernels:

>>> 2 * EQ() == EQ() + EQ() True >>> EQ() + Exp() == Exp() + EQ() True >>> 2 * Exp() == EQ() + Exp() False >>> EQ() + Exp() + Linear() == Linear() + Exp() + EQ() # Too hard: cannot prove equality! False

-

The stationarity of a kernel

kcan always be determined by queryingk.stationary.Example of querying the stationarity:

>>> EQ().stationary True >>> (EQ() + Linear()).stationary False

The examples make use of Varz and some utility from WBML.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from wbml.plot import tweak

from stheno import B, Measure, GP, EQ, Delta

# Define points to predict at.

x = B.linspace(0, 10, 100)

x_obs = B.linspace(0, 7, 20)

# Construct a prior.

prior = Measure()

f = GP(EQ().periodic(5.0), measure=prior) # Latent function

e = GP(Delta(), measure=prior) # Noise

y = f + 0.5 * e

# Sample a true, underlying function and observations.

f_true, y_obs = prior.sample(f(x), y(x_obs))

# Now condition on the observations to make predictions.

post = prior | (y(x_obs), y_obs)

mean, lower, upper = post(f)(x).marginals()

# Plot result.

plt.plot(x, f_true, label="True", style="test")

plt.scatter(x_obs, y_obs, label="Observations", style="train", s=20)

plt.plot(x, mean, label="Prediction", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower, upper, style="pred")

tweak()

plt.savefig("readme_example1_simple_regression.png")

plt.show()import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from wbml.plot import tweak

from stheno import Measure, GP, EQ, RQ, Linear, Delta, Exp, B

B.epsilon = 1e-10

# Define points to predict at.

x = B.linspace(0, 10, 200)

x_obs = B.linspace(0, 7, 50)

# Construct a latent function consisting of four different components.

prior = Measure()

f_smooth = GP(EQ(), measure=prior)

f_wiggly = GP(RQ(1e-1).stretch(0.5), measure=prior)

f_periodic = GP(EQ().periodic(1.0), measure=prior)

f_linear = GP(Linear(), measure=prior)

f = f_smooth + f_wiggly + f_periodic + 0.2 * f_linear

# Let the observation noise consist of a bit of exponential noise.

e_indep = GP(Delta(), measure=prior)

e_exp = GP(Exp(), measure=prior)

e = e_indep + 0.3 * e_exp

# Sum the latent function and observation noise to get a model for the observations.

y = f + 0.5 * e

# Sample a true, underlying function and observations.

(

f_true_smooth,

f_true_wiggly,

f_true_periodic,

f_true_linear,

f_true,

y_obs,

) = prior.sample(f_smooth(x), f_wiggly(x), f_periodic(x), f_linear(x), f(x), y(x_obs))

# Now condition on the observations and make predictions for the latent function and

# its various components.

post = prior | (y(x_obs), y_obs)

pred_smooth = post(f_smooth(x)).marginals()

pred_wiggly = post(f_wiggly(x)).marginals()

pred_periodic = post(f_periodic(x)).marginals()

pred_linear = post(f_linear(x)).marginals()

pred_f = post(f(x)).marginals()

# Plot results.

def plot_prediction(x, f, pred, x_obs=None, y_obs=None):

plt.plot(x, f, label="True", style="test")

if x_obs is not None:

plt.scatter(x_obs, y_obs, label="Observations", style="train", s=20)

mean, lower, upper = pred

plt.plot(x, mean, label="Prediction", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower, upper, style="pred")

tweak()

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.subplot(3, 1, 1)

plt.title("Prediction")

plot_prediction(x, f_true, pred_f, x_obs, y_obs)

plt.subplot(3, 2, 3)

plt.title("Smooth Component")

plot_prediction(x, f_true_smooth, pred_smooth)

plt.subplot(3, 2, 4)

plt.title("Wiggly Component")

plot_prediction(x, f_true_wiggly, pred_wiggly)

plt.subplot(3, 2, 5)

plt.title("Periodic Component")

plot_prediction(x, f_true_periodic, pred_periodic)

plt.subplot(3, 2, 6)

plt.title("Linear Component")

plot_prediction(x, f_true_linear, pred_linear)

plt.savefig("readme_example2_decomposition.png")

plt.show()import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import tensorflow as tf

import wbml.out as out

from varz.spec import parametrised, Positive

from varz.tensorflow import Vars, minimise_l_bfgs_b

from wbml.plot import tweak

from stheno.tensorflow import B, Measure, GP, EQ, Delta

# Define points to predict at.

x = B.linspace(tf.float64, 0, 5, 100)

x_obs = B.linspace(tf.float64, 0, 3, 20)

@parametrised

def model(

vs,

u_var: Positive = 0.5,

u_scale: Positive = 0.5,

e_var: Positive = 0.5,

alpha: Positive = 1.2,

):

prior = Measure()

# Random fluctuation:

u = GP(u_var * EQ() > u_scale, measure=prior)

# Noise:

e = GP(e_var * Delta(), measure=prior)

# Construct model:

f = u + (lambda x: x ** alpha)

y = f + e

return f, y

# Sample a true, underlying function and observations.

vs = Vars(tf.float64)

f_true = x ** 1.8 + B.sin(2 * B.pi * x)

f, y = model(vs)

post = f.measure | (f(x), f_true)

y_obs = post(f(x_obs)).sample()

def objective(vs):

f, y = model(vs)

evidence = y(x_obs).logpdf(y_obs)

return -evidence

# Learn hyperparameters.

minimise_l_bfgs_b(tf.function(objective, autograph=False), vs)

f, y = model(vs)

# Print the learned parameters.

out.kv("Prior", y.display(out.format))

vs.print()

# Condition on the observations to make predictions.

post = f.measure | (y(x_obs), y_obs)

mean, lower, upper = post(f(x)).marginals()

# Plot result.

plt.plot(x, B.squeeze(f_true), label="True", style="test")

plt.scatter(x_obs, B.squeeze(y_obs), label="Observations", style="train", s=20)

plt.plot(x, mean, label="Prediction", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower, upper, style="pred")

tweak()

plt.savefig("readme_example3_parametric.png")

plt.show()import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from wbml.plot import tweak

from stheno import B, Measure, GP, EQ, Delta

class VGP:

"""A vector-valued GP."""

def __init__(self, ps):

self.ps = ps

def __add__(self, other):

return VGP([f + g for f, g in zip(self.ps, other.ps)])

def lmatmul(self, A):

m, n = A.shape

ps = [0 for _ in range(m)]

for i in range(m):

for j in range(n):

ps[i] += A[i, j] * self.ps[j]

return VGP(ps)

# Define points to predict at.

x = B.linspace(0, 10, 100)

x_obs = B.linspace(0, 10, 10)

# Model parameters:

m = 2

p = 4

H = B.randn(p, m)

# Construct latent functions.

prior = Measure()

us = VGP([GP(EQ(), measure=prior) for _ in range(m)])

fs = us.lmatmul(H)

# Construct noise.

e = VGP([GP(0.5 * Delta(), measure=prior) for _ in range(p)])

# Construct observation model.

ys = e + fs

# Sample a true, underlying function and observations.

samples = prior.sample(*(p(x) for p in fs.ps), *(p(x_obs) for p in ys.ps))

fs_true, ys_obs = samples[:p], samples[p:]

# Compute the posterior and make predictions.

post = prior | (*((p(x_obs), y_obs) for p, y_obs in zip(ys.ps, ys_obs)),)

preds = [post(p(x)).marginals() for p in fs.ps]

# Plot results.

def plot_prediction(x, f, pred, x_obs=None, y_obs=None):

plt.plot(x, f, label="True", style="test")

if x_obs is not None:

plt.scatter(x_obs, y_obs, label="Observations", style="train", s=20)

mean, lower, upper = pred

plt.plot(x, mean, label="Prediction", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower, upper, style="pred")

tweak()

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

for i in range(4):

plt.subplot(2, 2, i + 1)

plt.title(f"Output {i + 1}")

plot_prediction(x, fs_true[i], preds[i], x_obs, ys_obs[i])

plt.savefig("readme_example4_multi-output.png")

plt.show()import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import tensorflow as tf

import wbml.plot

from stheno.tensorflow import B, Measure, GP, EQ, Delta

# Define points to predict at.

x = B.linspace(tf.float64, 0, 10, 200)

x_obs = B.linspace(tf.float64, 0, 10, 10)

# Construct the model.

prior = Measure()

f = 0.7 * GP(EQ(), measure=prior).stretch(1.5)

e = 0.2 * GP(Delta(), measure=prior)

# Construct derivatives.

df = f.diff()

ddf = df.diff()

dddf = ddf.diff() + e

# Fix the integration constants.

zero = B.cast(tf.float64, 0)

one = B.cast(tf.float64, 1)

prior = prior | ((f(zero), one), (df(zero), zero), (ddf(zero), -one))

# Sample observations.

y_obs = B.sin(x_obs) + 0.2 * B.randn(*x_obs.shape)

# Condition on the observations to make predictions.

post = prior | (dddf(x_obs), y_obs)

# And make predictions.

pred_iiif = post(f)(x).marginals()

pred_iif = post(df)(x).marginals()

pred_if = post(ddf)(x).marginals()

pred_f = post(dddf)(x).marginals()

# Plot result.

def plot_prediction(x, f, pred, x_obs=None, y_obs=None):

plt.plot(x, f, label="True", style="test")

if x_obs is not None:

plt.scatter(x_obs, y_obs, label="Observations", style="train", s=20)

mean, lower, upper = pred

plt.plot(x, mean, label="Prediction", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower, upper, style="pred")

wbml.plot.tweak()

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.subplot(2, 2, 1)

plt.title("Function")

plot_prediction(x, np.sin(x), pred_f, x_obs=x_obs, y_obs=y_obs)

plt.subplot(2, 2, 2)

plt.title("Integral of Function")

plot_prediction(x, -np.cos(x), pred_if)

plt.subplot(2, 2, 3)

plt.title("Second Integral of Function")

plot_prediction(x, -np.sin(x), pred_iif)

plt.subplot(2, 2, 4)

plt.title("Third Integral of Function")

plot_prediction(x, np.cos(x), pred_iiif)

plt.savefig("readme_example5_integration.png")

plt.show()import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import wbml.out as out

from wbml.plot import tweak

from stheno import B, Measure, GP, Delta

# Define points to predict at.

x = B.linspace(0, 10, 200)

x_obs = B.linspace(0, 10, 10)

# Construct the model.

prior = Measure()

slope = GP(1, measure=prior)

intercept = GP(5, measure=prior)

f = slope * (lambda x: x) + intercept

e = 0.2 * GP(Delta(), measure=prior) # Noise model

y = f + e # Observation model

# Sample a slope, intercept, underlying function, and observations.

true_slope, true_intercept, f_true, y_obs = prior.sample(

slope(0), intercept(0), f(x), y(x_obs)

)

# Condition on the observations to make predictions.

post = prior | (y(x_obs), y_obs)

mean, lower, upper = post(f(x)).marginals()

out.kv("True slope", true_slope[0, 0])

out.kv("Predicted slope", post(slope(0)).mean[0, 0])

out.kv("True intercept", true_intercept[0, 0])

out.kv("Predicted intercept", post(intercept(0)).mean[0, 0])

# Plot result.

plt.plot(x, f_true, label="True", style="test")

plt.scatter(x_obs, y_obs, label="Observations", style="train", s=20)

plt.plot(x, mean, label="Prediction", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower, upper, style="pred")

tweak()

plt.savefig("readme_example6_blr.png")

plt.show()import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import tensorflow as tf

from varz.spec import parametrised, Positive

from varz.tensorflow import Vars, minimise_l_bfgs_b

from wbml.plot import tweak

from stheno.tensorflow import B, Measure, GP, Delta, EQ

# Define points to predict at.

x = B.linspace(tf.float64, 0, 10, 200)

x_obs1 = B.linspace(tf.float64, 0, 10, 30)

inds2 = np.random.permutation(len(x_obs1))[:10]

x_obs2 = B.take(x_obs1, inds2)

# Construction functions to predict and observations.

f1_true = B.sin(x)

f2_true = B.sin(x) ** 2

y1_obs = B.sin(x_obs1) + 0.1 * B.randn(*x_obs1.shape)

y2_obs = B.sin(x_obs2) ** 2 + 0.1 * B.randn(*x_obs2.shape)

@parametrised

def model(

vs,

var1: Positive = 1,

scale1: Positive = 1,

noise1: Positive = 0.1,

var2: Positive = 1,

scale2: Positive = 1,

noise2: Positive = 0.1,

):

# Construct model for first layer:

prior1 = Measure()

f1 = GP(var1 * EQ() > scale1, measure=prior1)

e1 = GP(noise1 * Delta(), measure=prior1)

y1 = f1 + e1

# Construct model for second layer:

prior2 = Measure()

f2 = GP(var2 * EQ() > scale2, measure=prior2)

e2 = GP(noise2 * Delta(), measure=prior2)

y2 = f2 + e2

return f1, y1, f2, y2

def objective(vs):

f1, y1, f2, y2 = model(vs)

x1 = x_obs1

x2 = B.stack(x_obs2, B.take(y1_obs, inds2), axis=1)

evidence = y1(x1).logpdf(y1_obs) + y2(x2).logpdf(y2_obs)

return -evidence

# Learn hyperparameters.

vs = Vars(tf.float64)

minimise_l_bfgs_b(objective, vs)

# Compute posteriors.

f1, y1, f2, y2 = model(vs)

x1 = x_obs1

x2 = B.stack(x_obs2, B.take(y1_obs, inds2), axis=1)

post1 = f1.measure | (y1(x1), y1_obs)

post2 = f2.measure | (y2(x2), y2_obs)

f1_post = post1(f1)

f2_post = post2(f2)

# Predict first output.

mean1, lower1, upper1 = f1_post(x).marginals()

# Predict second output with Monte Carlo.

samples = [

f2_post(B.stack(x, f1_post(x).sample()[:, 0], axis=1)).sample()[:, 0]

for _ in range(100)

]

mean2 = np.mean(samples, axis=0)

lower2 = np.percentile(samples, 2.5, axis=0)

upper2 = np.percentile(samples, 100 - 2.5, axis=0)

# Plot result.

plt.figure()

plt.subplot(2, 1, 1)

plt.title("Output 1")

plt.plot(x, f1_true, label="True", style="test")

plt.scatter(x_obs1, y1_obs, label="Observations", style="train", s=20)

plt.plot(x, mean1, label="Prediction", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower1, upper1, style="pred")

tweak()

plt.subplot(2, 1, 2)

plt.title("Output 2")

plt.plot(x, f2_true, label="True", style="test")

plt.scatter(x_obs2, y2_obs, label="Observations", style="train", s=20)

plt.plot(x, mean2, label="Prediction", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower2, upper2, style="pred")

tweak()

plt.savefig("readme_example7_gpar.png")

plt.show()import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import tensorflow as tf

from varz.spec import parametrised, Positive

from varz.tensorflow import Vars, minimise_adam

from wbml.net import rnn as rnn_constructor

from wbml.plot import tweak

from stheno.tensorflow import B, Measure, GP, Delta, EQ

# Increase regularisation because we are dealing with `tf.float32`s.

B.epsilon = 1e-6

# Construct points which to predict at.

x = B.linspace(tf.float32, 0, 1, 100)[:, None]

inds_obs = B.range(0, int(0.75 * len(x))) # Train on the first 75% only.

x_obs = B.take(x, inds_obs)

# Construct function and observations.

# Draw random modulation functions.

a_true = GP(1e-2 * EQ().stretch(0.1))(x).sample()

b_true = GP(1e-2 * EQ().stretch(0.1))(x).sample()

# Construct the true, underlying function.

f_true = (1 + a_true) * B.sin(2 * np.pi * 7 * x) + b_true

# Add noise.

y_true = f_true + 0.1 * B.randn(*f_true.shape)

# Normalise and split.

f_true = (f_true - B.mean(y_true)) / B.std(y_true)

y_true = (y_true - B.mean(y_true)) / B.std(y_true)

y_obs = B.take(y_true, inds_obs)

@parametrised

def model(

vs, a_scale: Positive = 0.1, b_scale: Positive = 0.1, noise: Positive = 0.01

):

prior = Measure()

# Construct an RNN.

f_rnn = rnn_constructor(

output_size=1, widths=(10,), nonlinearity=B.tanh, final_dense=True

)

# Set the weights for the RNN.

num_weights = f_rnn.num_weights(input_size=1)

weights = Vars(tf.float32, source=vs.get(shape=(num_weights,), name="rnn"))

f_rnn.initialise(input_size=1, vs=weights)

# Construct GPs that modulate the RNN.

a = GP(1e-2 * EQ().stretch(a_scale), measure=prior)

b = GP(1e-2 * EQ().stretch(b_scale), measure=prior)

e = GP(noise * Delta(), measure=prior)

# GP-RNN model:

f_gp_rnn = (1 + a) * (lambda x: f_rnn(x)) + b

y_gp_rnn = f_gp_rnn + e

return f_rnn, f_gp_rnn, y_gp_rnn, a, b

def objective_rnn(vs):

f_rnn, _, _, _, _ = model(vs)

return B.mean((f_rnn(x_obs) - y_obs) ** 2)

def objective_gp_rnn(vs):

_, _, y_gp_rnn, _, _ = model(vs)

evidence = y_gp_rnn(x_obs).logpdf(y_obs)

return -evidence

# Pretrain the RNN.

vs = Vars(tf.float32)

minimise_adam(

tf.function(objective_rnn, autograph=False), vs, rate=1e-2, iters=1000, trace=True

)

# Jointly train the RNN and GPs.

minimise_adam(

tf.function(objective_gp_rnn, autograph=False),

vs,

rate=1e-3,

iters=1000,

trace=True,

)

_, f_gp_rnn, y_gp_rnn, a, b = model(vs)

# Condition.

post = f_gp_rnn.measure | (y_gp_rnn(x_obs), y_obs)

# Predict and plot results.

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.subplot(2, 1, 1)

plt.title("$(1 + a)\\cdot {}$RNN${} + b$")

plt.plot(x, f_true, label="True", style="test")

plt.scatter(x_obs, y_obs, label="Observations", style="train", s=20)

mean, lower, upper = post(f_gp_rnn(x)).marginals()

plt.plot(x, mean, label="Prediction", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower, upper, style="pred")

tweak()

plt.subplot(2, 2, 3)

plt.title("$a$")

mean, lower, upper = post(a(x)).marginals()

plt.plot(x, mean, label="Prediction", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower, upper, style="pred")

tweak()

plt.subplot(2, 2, 4)

plt.title("$b$")

mean, lower, upper = post(b(x)).marginals()

plt.plot(x, mean, label="Prediction", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower, upper, style="pred")

tweak()

plt.savefig(f"readme_example8_gp-rnn.png")

plt.show()import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from wbml.plot import tweak

from stheno import B, Measure, GP, EQ

# Define points to predict at.

x = B.linspace(0, 10, 100)

# Construct a prior.

prior = Measure()

f1 = GP(3, EQ(), measure=prior)

f2 = GP(3, EQ(), measure=prior)

# Compute the approximate product.

f_prod = f1 * f2

# Sample two functions.

s1, s2 = prior.sample(f1(x), f2(x))

# Predict.

post = prior | ((f1(x), s1), (f2(x), s2))

mean, lower, upper = post(f_prod(x)).marginals()

# Plot result.

plt.plot(x, s1, label="Sample 1", style="train")

plt.plot(x, s2, label="Sample 2", style="train", ls="--")

plt.plot(x, s1 * s2, label="True product", style="test")

plt.plot(x, mean, label="Approximate posterior", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower, upper, style="pred")

tweak()

plt.savefig("readme_example9_product.png")

plt.show()import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import wbml.out as out

from wbml.plot import tweak

from stheno import B, Measure, GP, EQ, Delta, SparseObs

# Define points to predict at.

x = B.linspace(0, 10, 100)

x_obs = B.linspace(0, 7, 50_000)

x_ind = B.linspace(0, 10, 20)

# Construct a prior.

prior = Measure()

f = GP(EQ().periodic(2 * B.pi), measure=prior) # Latent function.

e = GP(Delta(), measure=prior) # Noise.

y = f + 0.5 * e

# Sample a true, underlying function and observations.

f_true = B.sin(x)

y_obs = B.sin(x_obs) + 0.5 * B.randn(*x_obs.shape)

# Now condition on the observations to make predictions.

obs = SparseObs(

f(x_ind), # Inducing points.

0.5 * e, # Noise process.

# Observations _without_ the noise process added on.

f(x_obs),

y_obs,

)

out.kv("ELBO", obs.elbo(prior))

post = prior | obs

mean, lower, upper = post(f(x)).marginals()

# Plot result.

plt.plot(x, f_true, label="True", style="test")

plt.scatter(

x_obs, y_obs, label="Observations", style="train", c="tab:green", alpha=0.35

)

plt.scatter(

x_ind,

obs.mu(prior)[:, 0],

label="Inducing Points",

style="train",

s=20,

)

plt.plot(x, mean, label="Prediction", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower, upper, style="pred")

tweak()

plt.savefig("readme_example10_sparse.png")

plt.show()import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from wbml.plot import tweak

from stheno import B, Measure, GP, EQ, Delta

# Define points to predict at.

x = B.linspace(0, 10, 100)

x_obs = B.linspace(0, 10, 20)

# Constuct a prior:

prior = Measure()

w = lambda x: B.exp(-(x ** 2) / 0.5) # Window

b = [(w * GP(EQ(), measure=prior)).shift(xi) for xi in x_obs] # Weighted basis funs

f = sum(b) # Latent function

e = GP(Delta(), measure=prior) # Noise

y = f + 0.2 * e # Observation model

# Sample a true, underlying function and observations.

f_true, y_obs = prior.sample(f(x), y(x_obs))

# Condition on the observations to make predictions.

post = prior | (y(x_obs), y_obs)

# Plot result.

for i, bi in enumerate(b):

mean, lower, upper = post(bi(x)).marginals()

kw_args = {"label": "Basis functions"} if i == 0 else {}

plt.plot(x, mean, style="pred2", **kw_args)

plt.plot(x, f_true, label="True", style="test")

plt.scatter(x_obs, y_obs, label="Observations", style="train", s=20)

mean, lower, upper = post(f(x)).marginals()

plt.plot(x, mean, label="Prediction", style="pred")

plt.fill_between(x, lower, upper, style="pred")

tweak()

plt.savefig("readme_example11_nonparametric_basis.png")

plt.show()